Back in their 1980 work A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari decided they had had it with trees. Their structure was not as simple as we’d come to believe, nor was the hierarchical model of Western thought they inspired. Philosophy was not some simple phylogeny growing out from Plato’s central trunk. “In nature,” Deleuze and Guattari wrote, “roots are taproots with a more multiple, lateral, and circular system of ramification.” There is no simple branching system, no clear, chronological causality from origin to terminus. “We’re tired of trees,” they continued. “We should stop believing in trees, roots, and radicles. They’ve made us suffer too much.”

Enter one of academia’s favourite buzzwords. The rhizome. Unlike the dichotomous model of trees, rhizomatic plants and fungus grow in all directions with no central point. “A rhizome as subterranean stem is absolutely different from roots and radicles,” Deleuze and Guattari explained. An interlinked structure without a central beginning or end. “Any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be. This is very different from the tree or root, which plots a point, fixes an order.”

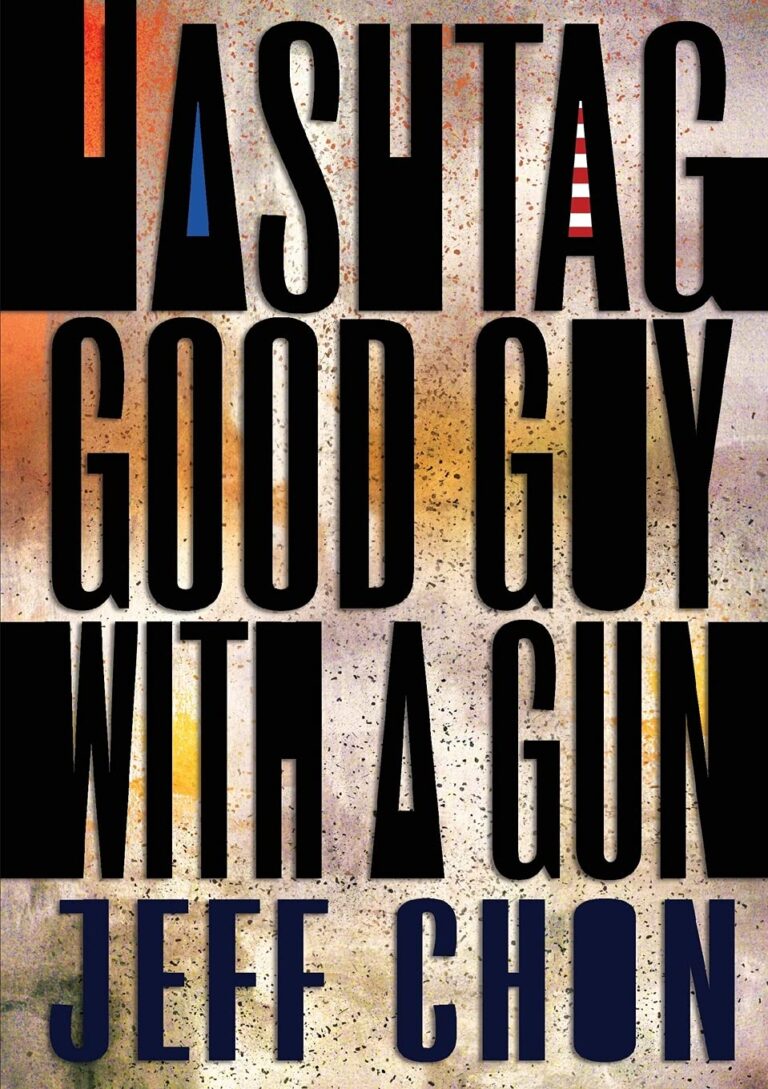

Jeff Chon’s debut novel, Hashtag Good Guy With a Gun, applies the rhizomatic model to our conspiratorial age. The narrative takes inspiration from the Comet Ping Pong incident, where a man drove from North Carolina to Washington D.C. armed with a semi-automatic rifle to attack a supposed Democratic Party child-sex ring operating from the basement of a pizzeria, though Chon adds further layers of complexity and irony to delve into the guts of such events. His protagonist Scott Bonneville walks into the Pizza Galley Family Fun Center and foils a would-be shooter—the titular Good Guy With a Gun—but he hadn’t arrived in search of the perfect slice. Bonneville was at the restaurant to carry out his own attack, motivated by a web of conspiracy theories and urban legends which, fertilised by our good friend toxic masculinity, manifest as a violent delusion both highly personal and strangely familiar.

Because in his own mind, Bonneville isn’t a conspiracy theorist. The moon landings certainly occurred, Earth’s roundness is not up for debate. You don’t have to be a card-carrying wacko to care about kids being exploited or kidnapped across the country. A little bit of your own research unveils clear links to law enforcement, schools and religious groups. Is it so wild to care about suffering kids? Then there is shady stuff involving Wall Street and the Carlyle Group, and the Bushes and Clintons, and the CIA and J.D. Salinger and Lee Harvey Oswald and Adrenochrome and and and…

“Conspiracy… is the poor person’s cognitive mapping in the postmodern age,” wrote Frederic Jameson. “A degraded figure of the total logic of late capital,” or, what he describes elsewhere “a degraded attempt […] to think the impossible totality of the contemporary world system.” But rather than representing a simplified fairy-tale version of global systems, the contemporary culture of conspiracy theory has morphed into its own impossible totality. In attempting to explain or reject the endless web of information, conspiracy theories come to represent a perfect example of the form. A rhizomatic structure key to their longevity and persistence. When the Pizzagate shooter pleaded guilty to assault with a dangerous weapon, Infowars‘ Alex Jones issued a statement acknowledging Comet Ping Pong was not involved in human trafficking. But the Democrat sex ring story was not demolished by the affirmation. Rather the Pizzagate conspiracy mutated to encompass the new developments, and now looks quaint compared with the scope and influence of QAnon. Take an axe to the trunk of a tree and every branch will wither and die. But sever a fungal rhizome and no such catastrophe occurs. The damage remains entirely local, the wider network no less capable of growth. “A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot,” wrote Deleuze and Guattari, “but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines. You can never get rid of ants because they form an animal rhizome that can rebound time and again after most of it has been destroyed.”

Chon brings this concept to life stylistically, circling the incident at the restaurant and providing glimpses into every occurrence and character which played some role in it, no matter how tangential. Hashtag Good Guy With a Gun comes to represent its own interlinked structure. The narrative is not linear. There is no present per se, just a series of scenes before, during and after the precipitating event. Vignettes presented out of order, and themselves prone to flashing back to some previous scene or revealing an as yet unrealised future. A story, for all of its male vanity and violent fervour, with no final villain or point of blame.

“You may make a rupture, draw a line of flight, yet there is still a danger that you will reencounter organizations that restratify everything.” Deleuze and Guattari could have been writing about Hashtag Good Guy With a Gun here. “Formations that restore power to a signifier, attributions that reconstitute a subject—anything you like, from Oedipal resurgences to fascist concretions.” And seeing as they, like Chon, were writing about this horrible world we have created, in a funny way they were.

Hashtag Good Guy With a Gun is out now via Sagging Meniscus Press. Get it from your local indie bookshop, or failing that Bookshop.org.