When writing Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, David Lipsky spent a lot of time in a car with David Foster Wallace. The Midwestern radio offered little beyond Green Day and shitty country music, and soon the sugary heartbreak and melodrama sent Lipsky up the wall. Country music used to have the same effect on Wallace, he reveals, but he’d since had something of an epiphany. What if even the most banal and superficial art has an underlying profundity? What if it is just a matter of looking beyond the surface, thinking deeper about what the words really mean? Maybe there is something shared between the fundamental and the individual, the grand and the glib? As Wallace put it:

These country musics that are just so—you know, ‘Baby since you’ve left I can’t live, I’m drinking all the time’ and stuff. And I remember just being real impatient with it […] And all of a sudden realised that, what if you just imagine that this absent lover they’re singing to is just a metaphor? And what they’re really singing is to themselves, or to God, you know? ‘Since you’ve left I’m so empty I can’t live, my life has no meaning.’

That in a weird way, I mean they’re incredibly existentialist songs. They have the patina of the absent, of the romantic shit on it just to make it saleable. But that all the pathos and heart that comes out of them, is they are singing about something much more elemental being missing, and their being incomplete without it. Than just, you know, some girl in tight jeans or something.

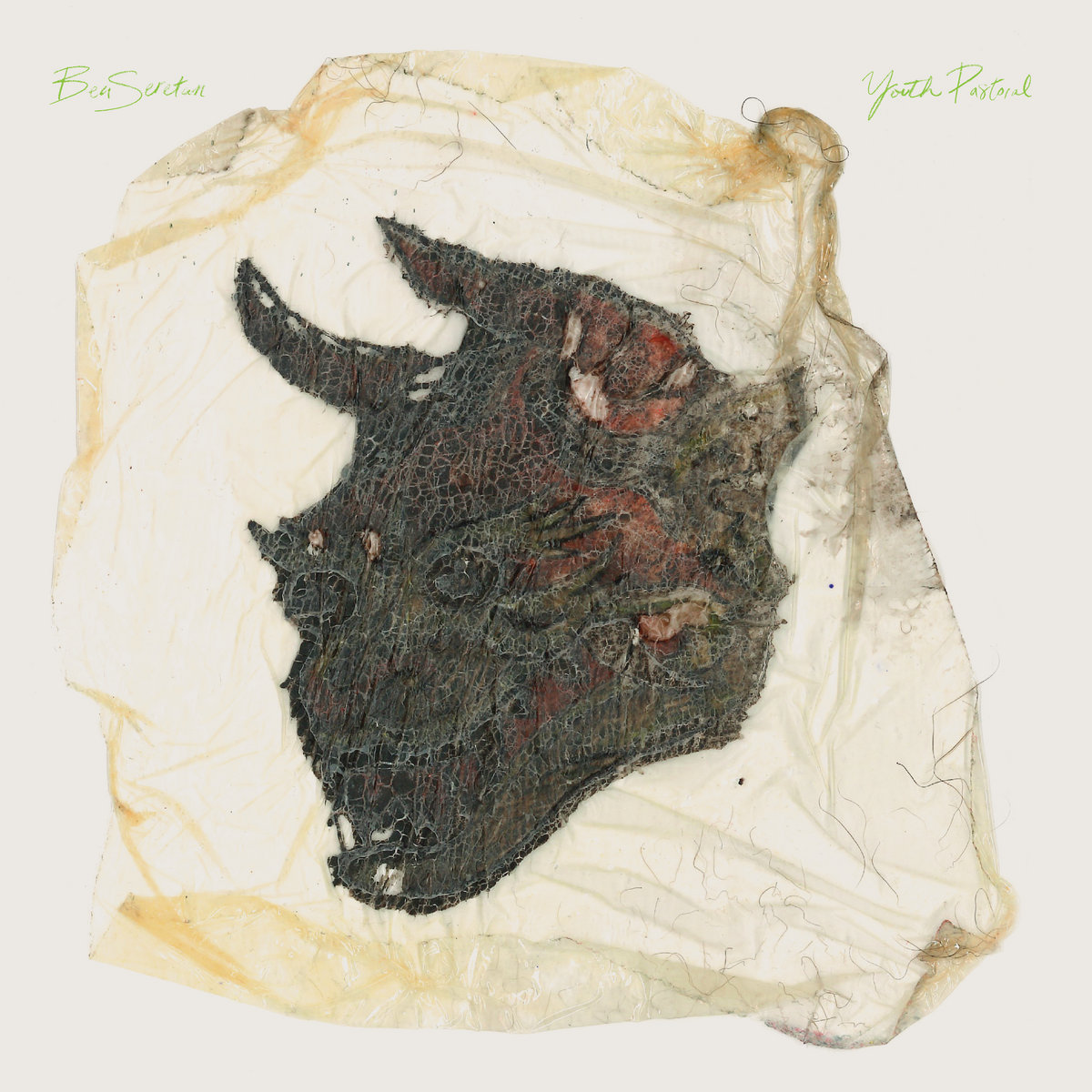

The music of Ben Seretan might not share much with the trite radio country, but if you buy into Wallace’s idea, then it might just share something. For Seretan’s latest record, Youth Pastoral, “zero[s] in on the significant overlap between breakup songs and lost god songs,” exploring how small moments of individual loss speak to a wider, existential longing, and how dealing with the first might inform our attempts to assuage the second. Be it personal or spiritual, relationships require a form of belief—belief in the possibility of love, and in the small day-to-day facts that prop this up—and finding private truths in which to believe, really believe, is surely the way out of the dark.

It’s been almost four years since the last Ben Seretan album, Bowl of Plums, (excluding the twenty-four-hour catalog of guitar drone, video and writing, titled My Life’s Work), a record he now describes as “incredibly optimistic, really sweet and kind of naive in its way.” A lot has happened since then, everything from personal difficulties to political upheaval showing Seretan that the worst can happen and often does. But rather than turning cynical with this chastening, Youth Pastoral is older and wiser but still bright, coming from a newfound sense of solidarity and security. In going through these trials, Seretan developed a surer sense of the person he really is, something that helps insulate him from transient change and outside influence. Validation is no longer the ultimate goal, for he believes in himself.

This is the most complex Ben Seretan record to date. The palette of Youth Pastoral is made up of darker shades than Bowl of Plums or his self-titled debut, but these only serve to highlight the bright notes. So while there is more balance—for every yelled line there’s a shimmering drone, each crashing cymbal balanced with the aching saw of lap steel or whispered sentiment—it only serves to underscore the underlying hope.

This is the most complex Ben Seretan record to date. The palette of Youth Pastoral is made up of darker shades than Bowl of Plums or his self-titled debut, but these only serve to highlight the bright notes. So while there is more balance—for every yelled line there’s a shimmering drone, each crashing cymbal balanced with the aching saw of lap steel or whispered sentiment—it only serves to underscore the underlying hope.

And, as though in knowledge of this, Seretan simply refuses to hold anything back. Like the best maximalists, he has too much to say, and an irresistible urge to say it. As though finally finding the language in which to communicate, you get the feeling the album is the opening of a metaphorical sluice gate, years and years of feelings rushing forth in one great wave. For all the wrestling with big metaphysical questions, the wrangling with dead ends both personal and spiritual, Youth Pastoral is suffused with a sense of joy.

One recurrent theme of the record is Seretan’s youth in California, particularly the image of his baptism in the Pacific surf. “In the ocean with my clothes on in late summer,” he sings on ‘Holding Up the Sun’, “hands on my head, hands on my back—hold me down.” The song is an explicit retelling of the actual event, and its accompanying video delves deeper into the moment. We’re delighted to be able to share it today, alongside an interview with Seretan that probes further still into Youth Pastoral, his responses delivered with the exact same passion and belief seen across the record.

You will always be hungry

for something you can’t hold

An Interview with…

Ben Seretan

It’s been almost four years since your last proper album. How does the new record differ from Bowl of Plums? What’s changed since then, and what, if anything, has stayed the same?

Bowl of Plums now strikes me as incredibly optimistic, really sweet and kind of naive in its way. A very well intentioned album that’s really deeply full of longing—I’m straining to hit the high notes, really striving for love and acceptance, both from within and without. That person that sings those songs strikes me as incredibly lonely, and kind of incredibly vulnerable—so open and so desiring, but unable to do the hard work of protecting their heart. And I think that’s why there’s a simplicity on some of the cuts—”twin bed” being just a simple song for piano and slide about a bed being too small, “I like your size” a quiet little song about someone saying something nice to you. These little lit matches of tenderness.

I’m still an incredibly optimistic person, I’m still in (a sometimes debilitating) constant need of tenderness, but—having been through the tumult and reshaping of the last four years—I just feel a different sense of strength, of fortitude and stability. I feel secure in myself, I think I need less validation from the outside world. And I think that’s reflected in the new songs.

Quite literally I’m a stronger person—I’ve been various degrees of obsessed with working out, running, and dancing for the last couple of years and my body has radically changed as a result (I feel like I talk about this a lot, but I lost ~60LBs in a year—that’s a lot!). And there’s an interior/exterior feedback loop there—the stronger I become, the better (I think) I look, the more confident and bold I get. So my attitude is very different—there’s a constant access to the body joy I was just starting to dare myself to feel in the music video for ‘Cottonwood Tree’.

And there are some pretty direct changes in the music—first of all, I listen to way more techno, house, disco, boogie type stuff, both while out dancing and on the treadmill, and there’s a pretty direct influence there. I really pushed Dan (from the band Adeline Hotel) to play those disco hi hats and groovier rhythms, particularly on ‘One Of’ and ‘Holding Up the Sun.’ I also really demanded low end presence in recording and mixing—Nico [Hedley]‘s bass playing is so prominent, the kick drum is huge, and all throughout mixing I kept asking Will to pump the low end. I wanted it to feel like the dance floor a bit, even when we’re playing the anthemic jammy indie rock stuff. There’s even a classic DJ move of rolling off the bass during the end of ‘Am I Doing Right by You.’ And then also my respiratory health is severely improved—my lungs are quite literally more healthy and stronger—and I think my singing has just gotten better. Not that it was bad before, but there’s a certain amount of ease (although the endearing lack of polish remains—no autotune, no doubling!).

[bandcamp width=100% height=120 album=3662684471 size=large bgcol=ffffff linkcol=0687f5 tracklist=false artwork=small track=99191687]

But in many ways Youth Pastoral is a “return to form.” It’s working within the accepted form of the album of songs, something we all know, something we all love! Guitar playing, singing, drums—we all know what’s happening here (and then I hope there are surprises and delights within the form). I spent much of 2017 – 2019 working on My Life’s Work, which is a massive undertaking I’m extremely proud of, but is so large and so unwieldy (it’s a 24-hour long collection of guitar drones with video and writing, for those unfamiliar) that it was kind of a way to keep a wall up. It was an exercise in being vulnerable and walled off at the same time. It was so big that you could never get your arms around it, and now I think I’m here, ready to embrace.

Ruefully I can’t help but note that Plums came out right before everything went to shit in American politics—I spent a long time after that record came out touring Europe and incorrectly reassuring folks that there was no way Donald Trump could win. So I associate that record with the belief that things in the world could never get all that bad. On a related note—the personal is political—things in my own life went to utter shit shortly after that, too, and similarly I incorrectly believed that things could never get that bad.

Obviously we’re in an election year now—there’s optimism on Youth Pastoral, but I think more than hoping for a better outcome there’s a powerful determination that strength and love are the things we have to rely on in order to make that better outcome a certainty. So it’s not “I sure hope the flowers bloom this year” but rather “I am going to till the earth, tend the seeds, and sweat it out on behalf of these little shoots of green.” (I’d also like to note here that we recently donated 24 hours worth of album sales to the Bernie Sanders campaign, those flowers are going to fucking bloom, goddamnit).

There are a few things that seem to hover around the album, the first being California, particularly in relation to your youth spent there. What are your memories of California, and in what way do these thoughts and images make it onto the album?

There is one central image on the record that is something I’ve come back to again and again.

When I was fourteen—just before I started high school and a few weeks before my parents decided to get a divorce—I ended the summer by participating in a group baptism organized by my church, held at the beach. We hung out and had a bonfire going and sung worship songs on acoustic guitars until the sun started sinking in the sky. The pastor overseeing it was wearing board shorts and Oakley sunglasses, I was wearing a special commemorative t-shirt and my mom had gotten an embroidered towel made.

The youth pastor—who I always point out, actually rode motocross and would show us clips of him doing jumps before his sermons—led me into the water, prayed over me, placed his hands on my back and forehead, and lowered me into the water. But instead of it being a calm, serene moment where I became more dedicated in my faith, I had the opposite experience—animal, primal fear, feeling like I was being held under—I quite literally was—and the salty ocean water I breathed in got in my lungs. I felt the corporeal world, I felt the air I sucked at when I came to the surface, as the sun set orange behind us.

This image is laid out explicitly in ‘Holding Up the Sun,’ which is a song (I think) about the desperation of faith—the repeated, gospel like mantra toward the end has a manic clawing to it. But the various dualities in that formative memory are everywhere on the record—above/below water, the corporeal and the ethereal, faith and fortitude, etc.

California has become increasingly edenic in my years away—it’s been like twelve years since I spent any significant amount of time there—and as it recedes in my memory it becomes warmer, lovelier, happier. I know my actual lived experience of California was complicated, full of smog and ennui, but when I think back on it now I can’t help but feel sea breezes, warm air, and coolness in the shade of palm trees. There’s a certain amount of all that present in the record.

And also I think the music I make will probably always be shaped by the experience of driving around late at night in southern California blasting CDs on my shitty sedan’s stereo—just having the most cathartic, chaotic, beautiful experiences listening to music at absolute full volume while blasting down the highway, the dark inky black of the Pacific off to one side. I get a bit of that feeling on the treadmill—the blasting, the catharsis—and I think I’m trying to capture that feeling of freedom and conveyance (even though I haven’t owned a car since I moved to the east coast).

Secondly, and I guess very much related, is the presence (or lack thereof) of God. Is that something you have come to terms with? And how did you go about filling that huge gap in your life?

I think California is a place where it is very easy to feel god’s presence. There are inspiring cliff sides and mountains jutting up out of the sea and beautiful scenery and perfect weather—”boring heaven,” you know? I’ve been riding the NYC subway every day for ten years and I think it’s much harder to bask in god’s light when you’re literally underground in a hurtling metal tube (I can imagine devils with pitchforks just beneath the substrata under the A train). I feel quite far from it, that light, but I’m comfortable here.

The triumph that’s felt or described in these songs, though, is one of moving out from under the shadow of a singular entity (god / a god-like force / a troubled love) into the many-armed embrace of collective humanity—that’s the whole vibe of “one of,” which is quite literally an attempt to describe the secular and corporeal ecstasy of really feeling yourself on the dance floor. In short, being a part of the world in my physical being is a much more potent and fulfilling substitute for the forces I held in my firmament.

Christianity as— it was handed down to me in Powerpoint presentations and wireless microphones—has a way of singling the believer out, of making the believer feel that their actions carry universal significance, that they have a direct relationship with the creator, that with one wrong thought or one wrong action they might damn themselves for eternity. Though you are surrounded by a congregation you are condemned for your sins by your acts alone.

And I later lived with someone who kept me in a similar position, one of thinking my damnation was only one error away. So although god—or someone assuming the mantle of a god—can provide order in an untidy universe, that figurehead also keeps a roadmap to your doom. I am very happy to be without the doom, I am very happy to be amongst the untidiness, and I am very happy that I feel in control of my own universe when I’m out dancing late at night.

[bandcamp width=100% height=120 album=3662684471 size=large bgcol=ffffff linkcol=0687f5 tracklist=false artwork=small track=329098232]

There’s a tangible sense of community on the record, and the list of collaborators is pretty long for what is ostensibly a solo record. How important are these other people, your friends, to this album?

Community is it! That’s the whole thing, the whole act of playing music or really doing anything at all that other people might listen to—the person singing and the person listening, that’s a community right there, that’s a complex ecosystem. I want these things to grow, that’s the whole thing.

There’s something I often find myself saying at shows—either ones that I’m playing or ones that I’m hosting in my living room. Basically, every time any group of people—no matter the size—gets together to hear music, it is quite literally a once-in-a-lifetime event. There will never be another moment where all these people, in quite this situation, will ever be gathered ever again. It happens just the once! And this extends to listeners of records, too—you’ll never hear the same album twice, just in the same way you’ll never step into the same stream twice. It’s very easy to be jaded, to think ah, this is just another show. But I try to keep these spaces sacred, as best as I can, because that community of people—particularly in that moment—is where I draw meaning.

I have earnestly felt this way for a long time, but the sacredness of gatherings was really severely underlined by the loss of our friend Devra last summer (I never know when to incorporate her into the narrative in talking about this record—she sings on the record, she was an incredible sculptor in addition to being a breezily brilliant musician, and we dedicate the record to her memory. I apologize if this is an inelegant way to bring it up, I still don’t know the best way to talk about it). Dev understood how special it was to get together—she was always, always happy to see other people, and really went out of her way to make you feel like you were having the best day of your life. She was this tremendous, important, life-changing force who had just started to be a part of our musical community and then, all of a sudden, she was utterly gone. Things like this, as terrible as it is to understand this, can and do happen. It’s almost trite to say but you have to love your friends, you have to love your community, because that light might go out one day.

As I said before, the turn of this record—why I believe it to be worth sharing—has to do with celebrating the notion of being a part of something made of people. One of. That’s partly why there are so many other voices included, both as singers and as instrumentalists—in order to sing about this lovely throng, I had to have it represented in some way. Plus, I am very fortunate to know and get to work with a wildly talented group of people—it’s easy to make a record sound good when there’s this much trust, love, and admiration going around. I can absolutely rely on Nico to play a beautiful and surprising bass line, for instance. I can’t really imagine making something without my friends’ fingerprints all over it, because what’s best and most interesting about me is the people I love.

Also, I should point out that this record is part of a really rad collective label effort we’ve got going. I started putting the name Whatever’s Clever on my own records starting with Bowl of Plums, but in May of 2019 Nico (with the sick bass lines) asked me if he could put out a 7″ on my label. And it grew from there—we’ve done a bunch of really cool releases by friends in our immediate circle, we’ve thrown a lot of incredibly beautiful shows in my living room, and we have a bunch of other stuff coming out soon, too. It’s a lightly organized effort toward putting our collective energies together and every day I’m prouder and more thankful that we’re rolling this boulder.

I think it’s fair to say this is the most complex and intense record you’ve made, there seem to be shadows that weren’t there before. Is this a conscious decision? Or the result of your added experience as a songwriter? Or are you just at a different period of your life?

It’s true, I think this record as it was written deals with some much heavier stuff than previous outings. A loss of innocence, in some ways, and an interest in portraying a loss of innocence, too. But once we lost our beloved collaborator it took on a completely different set of meanings. I’ve done a lot of mourning in finishing the record, in packaging, in sharing it with the world. I’ve worked out my grief in hearing these songs, featuring our friend’s voice, again and again and again. And recently—playing these songs live with an 8-piece band at the release show—I worked through other aspects of loss. I think those shadows came to the surface once the record changed in that way. Some of the darkness that was already there came to the fore.

But I also personally really went through the wringer between my last record and this one—I experienced some unprecedented darkness in my life (which had admittedly been pretty sunny up until that point). A lot of these songs were written at a time when I felt completely chewed up and spit out, just at a loss for what to even do with myself and kind of out of options. ‘Power Zone,’ in particular, was written as a kind of act of survival. A first footstep forward.

But that darkness makes the hope and the joy even more powerful, no?

[bandcamp width=100% height=120 album=3662684471 size=large bgcol=ffffff linkcol=0687f5 tracklist=false artwork=small track=2891518024]

Despite that, there is still that electric current of irrepressible joy that runs though everything. How do you maintain that? And how can other people find it too (aside from listening to the record!)?

Here is a list of things that consistently bring me joy, perhaps these will work for some of your readers:

- running on the treadmill listening to disco and getting deep into my second wind

- when the drums and the cymbals get so loud that they’re kind of painful

- successfully taking a ferry to somewhere you need to be

- eating food that’s so spicy you kind of lightly start to hallucinate

- staying out really late dancing, preferably until the sun comes up (and then hearing the birds in the trees on your walk home)

- loud dance music where you can feel the bass drum in your stomach

- gathering your favorite friends together in your living room to peacefully listen to music, preferably while drinking hot tea

- going for runs outside in new places and cities

- ripping an incredibly over the top guitar solo that maybe goes on too long and definitely features some wrong notes

- sitting for a long time in the Russian and Turkish Baths on east 10th street

- when the fog from the fog machine is so thick you can’t even see your buddy next to you

- dancing so hard that when you walk out into the night winter air steam rises from your body

Youth Pastoral is out now and you can get it from the Ben Seretan Bandcamp page.

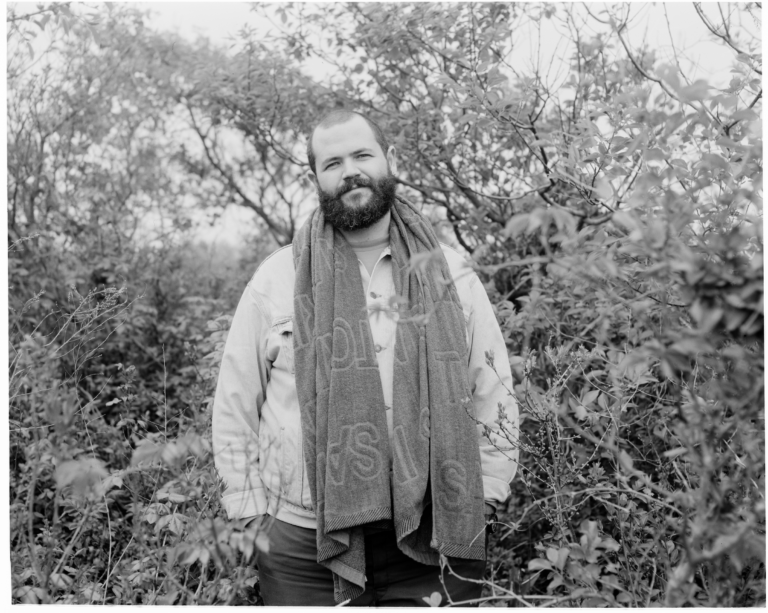

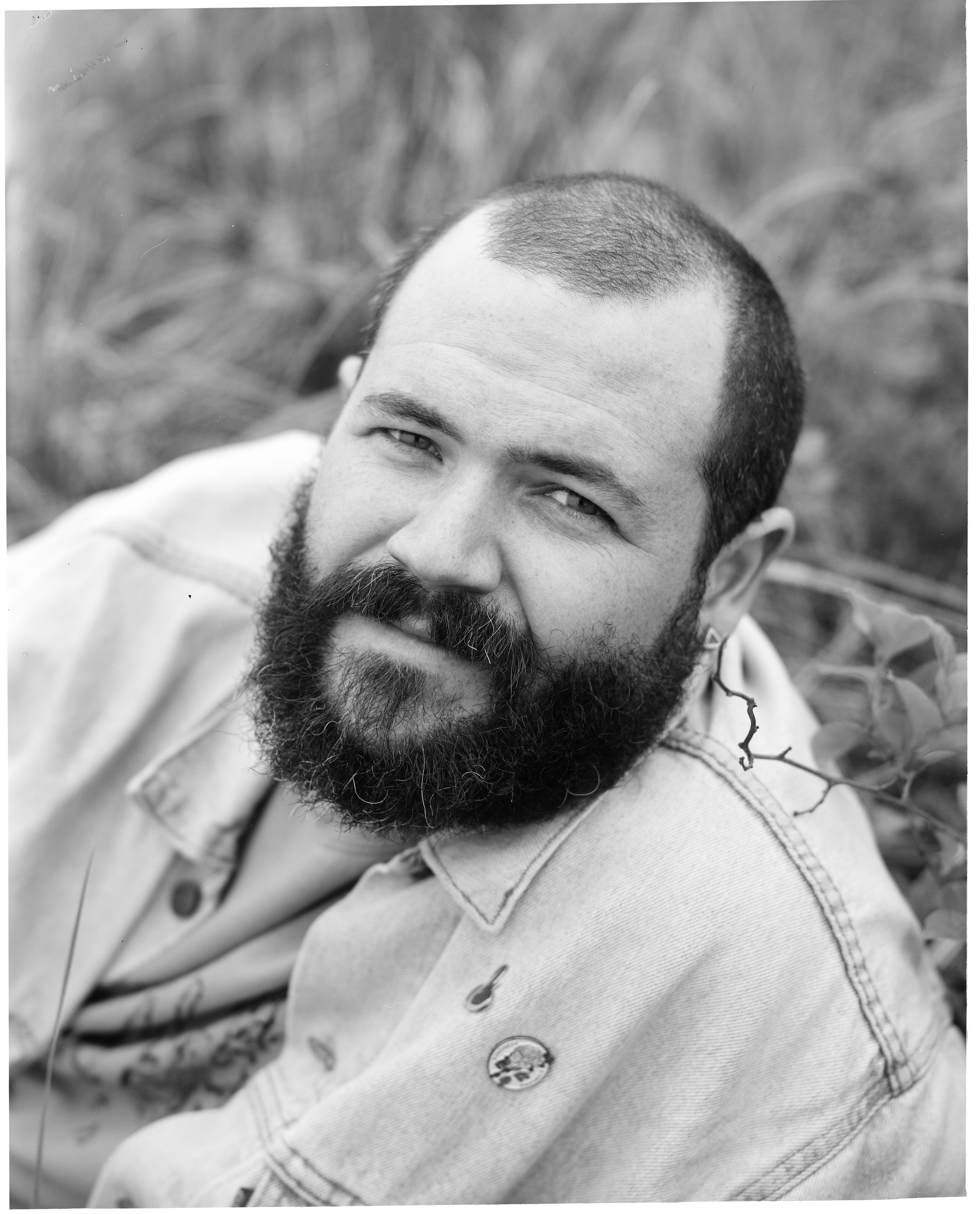

Colour photos by Brian Vu, black and white by Caiti Borruso