I mentioned Amelia Gray’s début novel Threats in my review of Young Jesus’s excellent Grow / Decompose, drawing parallels in the way the characters dissociate from ‘normal’ behaviour and retreat into their own strange worlds. As I wrote of Threats:

“[David] descends the spirals of grief after losing his wife… With death and decay quite literally pervading his house and life, David finds himself both terrified by his situation yet drawn towards some obscure peace with it, as if giving in to a dark and fungal siren”

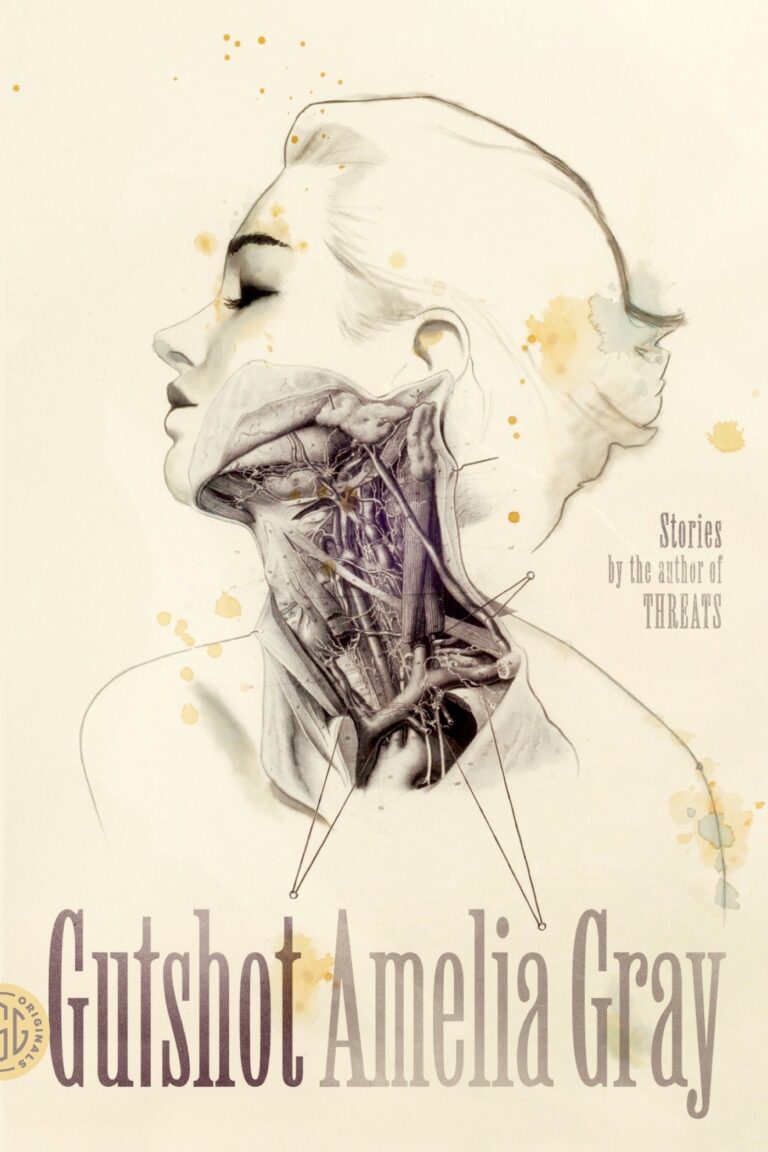

Amelia Gray is back with her third collection of short stories, Gutshot. As the title suggests, this is an uncomfortable book. Like, being-shot-square-in-the-guts level uncomfortable. There’s a man who vomits every time he speaks (and carries an empty pop bottle for convenience), mutual genital mutilation between a couple struggling to conceive a child, a family who carve up an over-sized heart with kitchen knives. There are giant snakes and desecrated graveyards and twins within twins. And yes, there is blood and shit and mucus in large quantities.

As in Threats, many of the characters in Gutshot seem aware of their situation but unable to change, as if passengers on a train called Life or Destiny which they understand will arrive at its destination regardless of anything they might do. These are people caught in a strange stases, pervaded by vague sensations they can see and feel but not avoid, sensations which eat away at their insides until they are hulled and hollow. Opener ‘In The Moment’ is a good example, a story where a couple eradicate all references of the past or future from their apartment, removing all context from their existence and thus making life at once fascinating and impossible. See also ‘Away From’, the tale of a kidnapped woman who freezes at the top of the stairs when trying to escape. Reading these stories is like watching a fungus bloom across a wall, like watching a slow-motion video of yourself going up in flames.

This feeling hangs over the majority of the stories, even those in which the characters are decisive. Even ‘The Labyrinth’, which sees a not-so-brave man decide to be brave teeters toward a cryptic ending, or rather ends cryptically before any real conclusion. This is typical Gray, never quite giving the reader that satisfying click of recognition, the realisation of where a story is going or what it means. Good people aren’t rewarded and bad people aren’t punished and even passages that first appear clear allegories or fables skew into confusion. In ‘The Labyrinth’, the narrator, Jim, is forced to carry an (heavy) enigmatic disk through the maze:

“I don’t know about this,” I said.

“It’s the Phiastos Disk,” Dale said. “I paid a pretty penny so mind where you set it.”

It did seem to be imbued with some significance.

And so Jim takes the disk into the labyrinth without ever understanding why. Gray’s grotesque imagery is much the same. It remains important, vital, to her work without serving any clear function (ie. any ham-fisted metaphorical purpose), as if its meaning is so large it’s impossible to focus on. ‘Year of the Snake’ is set up like a strange and ambiguous fairy tale that never narrows down to some moral principle, while ‘The Swan as Metaphor for Love’ begins like an amusing love-is-actually-terrible gag before subverting the subversion, delving so far into horrible, biological truths that you’re left with an existential consideration so primal it registers as a taste in the mouth.

I could go on: ‘Device,’ ‘These Are Fables’ and the title story all seem to tee up some valuable punchline without following through, highlighting something that makes Gray’s writing so special. By not giving answers, or sending explicit messages, she manages to create characters and situations which feel real despite their surreality. Whether they have a device which can predict the future, an unending compulsion to say thank you or a prostitute locked in the heating ducts of their home, each and every character is vividly, fatally, human.

To review the collection as a whole is a difficult job. The book reads like a carefully constructed chaos too nuanced to be unified into a clear theme. Occasionally an image or theme is amplified by what seems like inadvertent recurrence, while other times they clash messily leaving once-clear messages and morals adrift in ambiguity. This gives Gray’s design an decidedly organic feel, each piece, ignorant of the rest, fulfils its own role as if it is the most important thing in the world, creating a system of blind parts working furiously toward some obscure goal, and giving Fernando Vicente‘s artwork a whole new meaning.

Gutshot is out now, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Seeing as we are primarily a music website, we thought we’d included a playlist of songs to accompany each book review. The tracks aren’t necessarily directly related to the anything in the stories, but rather get close to the same sorts of imagery and moods. Enjoy.

2. Fabulous Muscles (Mama Black Widow) – Xiu Xiu

3. That Battle Is Over – Jenny Hval

4. The Bone – Kathryn Joseph

5. Drunk Walk Home – Mitski

6. Eat Your Heart Up – The Blow

7. Jane – Girlpool

8. These Few Presidents – Why?

9. Blood and Guts – Young Jesus

10. Love Connection – Casiotone For The Painfully Alone